My previous article on “the lost meaning of ideology” explored how Marx’s critical, negative, and objective concept has been eclipsed by a neutral, positive, and subjective account. One daily encounters so many references to “my ideology,” “their ideologies,” “liberal ideology,” “conservative ideology,” etc., that they blur together, making it difficult to isolate a single example of this pluralistic treatment of ideology as one set of beliefs among many. Yet there is one recent piece of ideology that inverts Marx’s concept so perfectly, so brazenly, and to such comic effect that it has stuck in my mind as something worth analyzing on its own.

The article in question, “A New Political Identity,” is a reminiscence of Occupy Wall Street written by Gabriel Winant to mark that event’s tenth anniversary for Dissent. In this piece, Winant, a history professor at the University of Chicago, cherishes Occupy as “the critical event in the formation of a novel anticapitalist intellectual milieu.” In doing so, he reveals a warped sense of ideology as an autonomous, positive realm shaped by the lived experiences of bourgeois intellectuals like himself.

Inverting Marx’s negative view of ideology as the distorted consciousness necessarily produced to harmonize social contradictions, Winant portrays it as a good in itself, something intellectuals may independently produce and spread to positive or even “anticapitalist” effect throughout the knowledge and culture industries they inhabit. This leads Winant to the optimistic conclusion that the Occupy “movement’s legacy is best understood as an episode in the history of ideology. It is at the level of ideology where it had its greatest effect—which is why it is so often, and wrongly, dismissed as having had no effect at all.”

Whereas others looking back on the past decade would be hard-pressed to discern how Occupy did anything to disrupt the capitalist development it protested, Winant defines the success of Occupy in terms of the formative influence its shared experience had on a budding generation of “ideological” workers in academia and other cultural fields. Occupy’s inability to transform the objective society is not important because, for Winant, it did something more profound: it changed the subjectivities of the important people whose experiences within Occupy would inform their professional roles in cultural institutions. Indeed, the participants “would change not the state but themselves, and then carry that change with them elsewhere.”

Winant’s celebration of Occupy Wall Street’s uplifting influence on a new generation of intellectual workers is such an ironic account of ideology because it glorifies what Marx criticizes. It unwittingly illustrates Marx’s view of ideology as the mental production of class society in which, for example, authorized intellectuals in bourgeois institutions like Winant manufacture ideology (e.g., tales of Occupy’s success) that papers over contradictions. Except whereas such ideological production is the object of criticism for Marx, Winant portrays it in a heroic light.

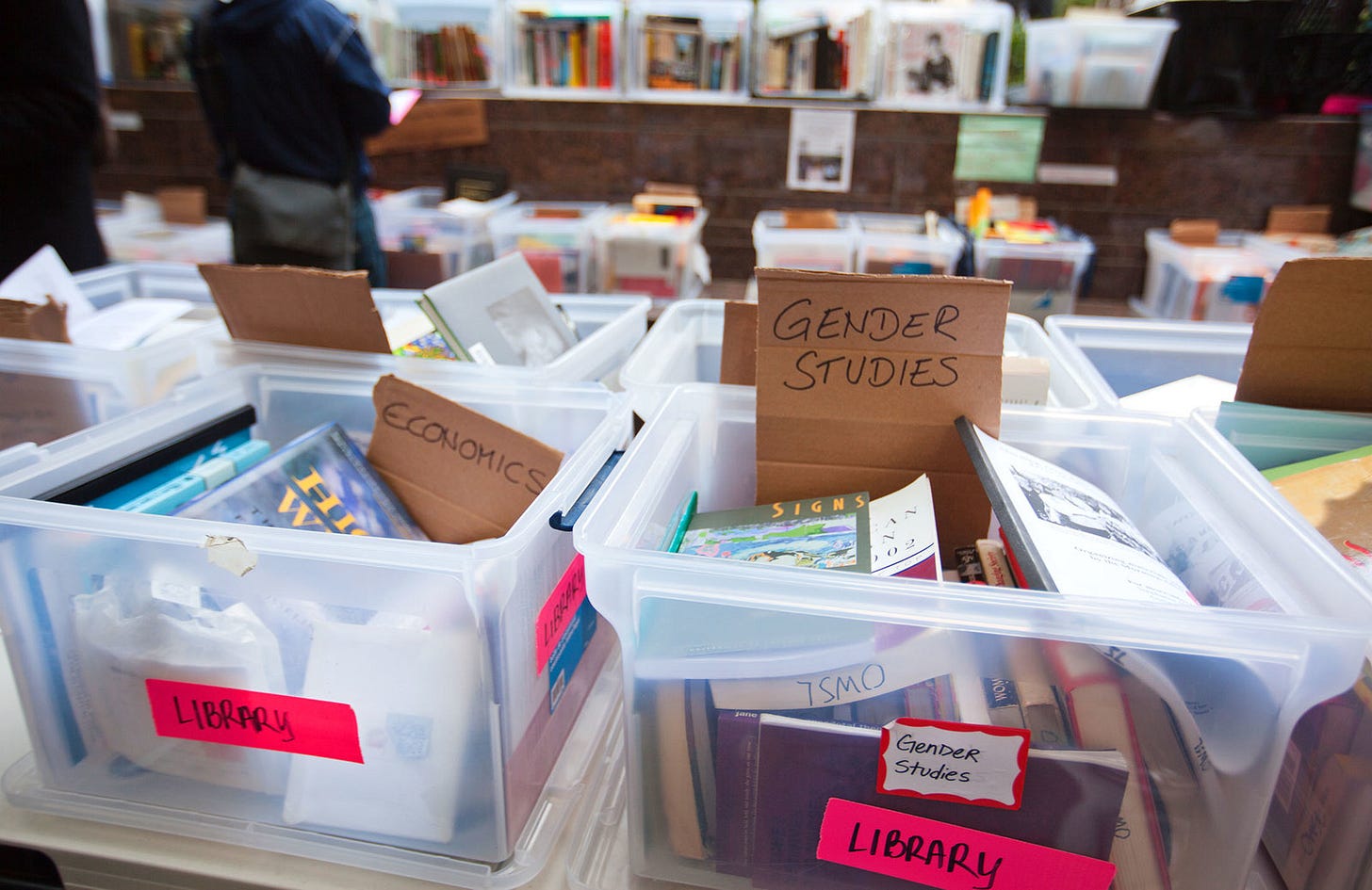

The humor of Winant’s piece indeed lies in its shameless romanticization of ivy-league academics and middle-class “cultural producers.” Unlike so much leftist propaganda that claims to speak for the common worker, Winant does nothing to hide the class nature of the ideologists nurtured by Occupy. The anticapitalist milieu formed around Occupy was “the world of the little magazines and radical publishers, the podcasters and the socialist activists,” the graduate students and professionals-in-training like himself who attended Occupy-themed Marxist reading groups, where they perhaps took Marx’s description of ideological production as a manual and not an object of criticism.

For Winant, the legacy of Occupy lives on in the institutions of ideology that were created or shaped by Zuccotti Park. Without Occupy, The New Inquiry and Jacobin would not have gained “their solidity.” n+1 and Dissent may not have undergone “much-heralded generational transformations, pointing them in newly radicalized directions.” This is not to speak of the Brooklyn Institue for Social Research that appeared in Occupy’s wake, “founded by left-wing Columbia graduate students looking for a meaningful alternative to dead-end academic careers.” “All this, it turns out, had consequences,” namely, in the consciousness of “the extended world of activists, writers, and thinkers” who took the spirit of Occupy into the institutional channels of academia, media, and politics.

To illustrate this, Winant recounts the day he spent in jail after an Occupy protest, where his holding cell included a who’s who of future ideological influencers. A decade later, they are now “publishing essays, writing history, leading labor and tenant organizing, working in electoral politics, making documentary films. (And—segregated as we were by gender—this was only the men.)” It was only an environment like Occupy that made it possible for these middle-class radicals “to construct a new political identity,” one responsible for the “recovery of left-wing politics” and “the rising workplace militancy of academics, journalists, museum workers, and other similar professional workers in the last decade.” In short, Occupy enhanced the class consciousness of those embittered young “ideological” workers “negotiating precarious” but inevitable “entries into the culture industries.”

Winant does express the basic Marxist insight that “institutions of culture” such as Jacobin magazine or the University of Chicago “produce and propagate ideology,” that ideological concepts don’t emerge from thin air but “require a material basis if they are to gain and keep purchase—groups of people whose job is to manufacture them, refine them, apply them, and spread them.” But where Winant’s theory of ideology becomes ideological itself—where it conceals social contradictions—is in its naive presentation of these insitutions as class-neutral vessels that can be put to various social purposes depending on the autonomous thought of those who happen to work within them.

In Winant’s story, his generation of professional intellectuals now use the means of ideological production they have assumed to create good anticapitalist ideology based on their shared Occupy experience. The “thousands who went on to do one kind of ideological work or another” have indeed “found a way to represent something of what Occupy had meant—or more generally, who they had become in 2011.” The triumph of Occupy is that it left an indelible impression on the anticapitalist professionals it created, like Winant who will carry its revolutionary torch as he ascends the tenure ladder at the University of Chicago.

Of course, for Marx, this is fantastical. In his critical conception, there is no good ideology, because ideology is necessarily produced by the contradictions of the society as a whole. There are not independent ideologists or institutions of ideology. State ideological organs such as academia and the media exist to produce the consciousness that facilitates the reproduction of the society. Those who secure salaried posts inside bourgeois institutions like Winant do not create ideology in an autonomous fashion based on their lived experiences. Rather, they only assume such positions insofar as they serve the ideological function of their institutions. In short, they do not produce ideology. They are themselves produced by ideology.

Ideologists like Winant occupy a position in the bourgeois “division of mental and material labour.” As Marx and Engels describe in The German Ideology, “inside this class one part appears as the thinkers of the class (its active, conceptive ideologists, who make the formation of the illusions of the class about itself their chief source of livelihood).”1 This is the service Winant provides in his role as a University of Chicago professor and in his romantic tales of Zucotti Park. Thanks to the ideology of Occupy, as he assures us, the ruling class is anticapitalist.

Marx and Engels, The German Ideology, in Marx-Engels Collected Works, Vol. 5. (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1976), 60.

I was at occupy and the fucking worst people came out of it. Even Tim Pool got his start there as he hung around being a fucking weirdo creep. The interesting things that came out of ows were people fed up with the bullshit of the hippy circle and the liberal nonsense. Some do nothing magazines having their roots in ows isn’t a sign of its success but rather how successfully it platformed careerist.

Again, apologies for reading this almost a year later. Another excellent essay, the best critique I"ve seen of Occupy, selecting the high points of Winant's assessment of it. I would add this: Early on, Winant highlights Michael Denning and quotes him: “The most significant consequence of Occupy, Denning predicted, would not be direct political victories, but rather the experience itself, the individual lessons it taught and the ways that it became embedded in the life histories of those who went through it. As in all intense social movement cycles, participants would find themselves doing things they would not have anticipated.... They would change not the state but themselves, and then carry that change with them elsewhere." Denning's view, and Winant's is politics as personal therapy. It has its roots in late sixties radicalism, particularly feminists who raised the slogan, the personal is the political. A consequence is that if radicals don’t feel better about themselves then what’s the point? (as I surely did at the time; then had to face the consequences in the mid-seventies…) Thus it was middle class malaise, what some left dissidents consider a spiritual emptiness in their lives, which motivated much radical activity. This would eventually defeat critique, including the left critiquing itself. For to critique your commitments, including your past attachments, you probably won't be feeling too good about yourself...